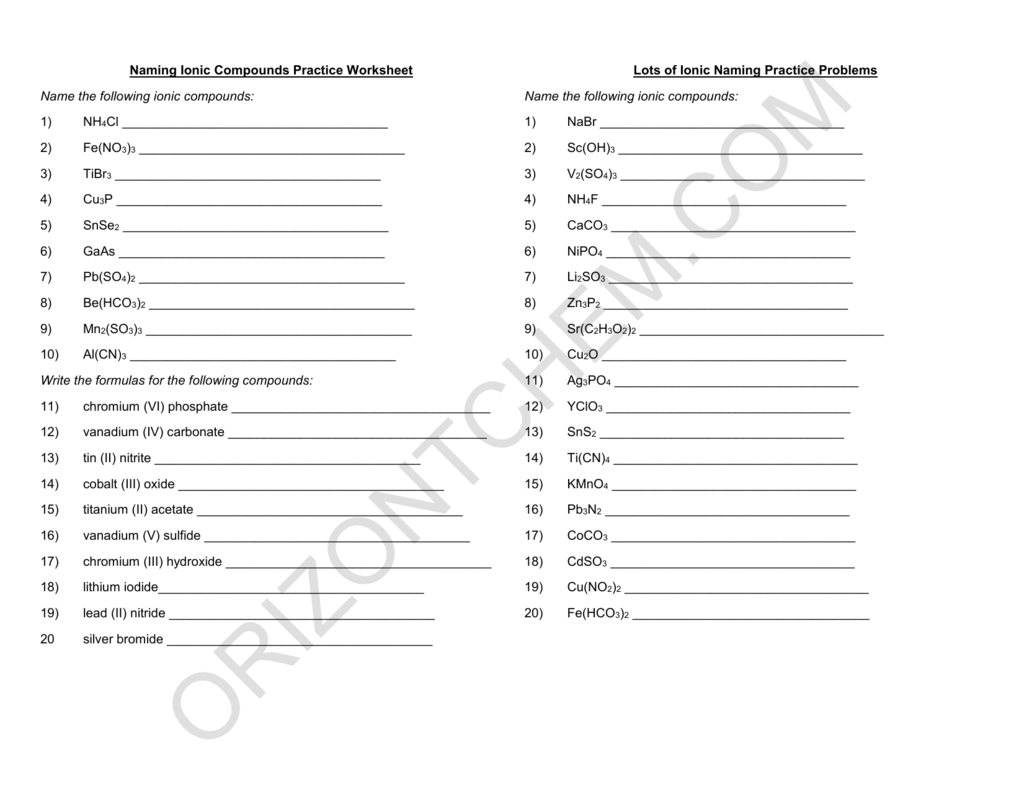

For example, on the label of your dentist’s fluoride rinse, the compound chemists call tin(II) fluoride is usually listed as stannous fluoride. Even though this text uses the systematic names with roman numerals, you should be able to recognize these common names because they are still often used. The names of Fe 3+, Fe 2+, Sn 4+, and Sn 2+ are therefore ferric, ferrous, stannic, and stannous, respectively. The name of the cation with the higher charge is formed from the root of the element’s Latin name with the suffix - ic attached, and the name of the cation with the lower charge has the same root with the suffix - ous. Thus Cu + is copper(I) (read as “copper one”), Fe 2+ is iron(II), Fe 3+ is iron(III), Sn 2+ is tin(II), and Sn 4+ is tin(IV).Īn older system of nomenclature for such cations is still widely used, however. In such cases, the positive charge on the metal is indicated by a roman numeral in parentheses immediately following the name of the metal. This behavior is observed for most transition metals, many actinides, and the heaviest elements of groups 13–15. As shown in Figure 2.11 "Metals That Form More Than One Cation and Their Locations in the Periodic Table", many metals can form more than one cation. For example, Na + is the sodium ion, Ca 2+ is the calcium ion, and Al 3+ is the aluminum ion. The name of the cation of a metal that forms only one cation is the same as the name of the metal (with the word ion added if the cation is by itself). As noted in Section 2.1 "Chemical Compounds", these metals are usually in groups 1–3, 12, and 13. Place the ions in their proper order: cation and then anion.The procedure for naming such compounds is outlined in Figure 2.10 "Naming an Ionic Compound" and uses the following steps:

We begin with binary ionic compounds, which contain only two elements. The objective of this and the next two sections is to teach you to write the formula for a simple inorganic compound from its name-and vice versa-and introduce you to some of the more frequently encountered common names.

Unfortunately, some chemicals that are widely used in commerce and industry are still known almost exclusively by their common names in such cases, you must be familiar with the common name as well as the systematic one. In this text, we use a systematic nomenclature to assign meaningful names to the millions of known substances. For example, the systematic name for KNO 3 is potassium nitrate, but its common name is saltpeter. Like the names of most elements, the common names of chemical compounds generally have historical origins, although they often appear to be unrelated to the compounds of interest. Many compounds, particularly those that have been known for a relatively long time, have more than one name: a common name (sometimes more than one) and a systematic name, which is the name assigned by adhering to specific rules. In such cases, it is necessary for the compounds to have different names that distinguish among the possible arrangements. For example, saying “C-A-three-P-O-four-two” for Ca 3(PO 4) 2 is much more difficult than saying “calcium phosphate.” In addition, you will see in Section 2.4 "Naming Covalent Compounds" that many compounds have the same empirical and molecular formulas but different arrangements of atoms, which result in very different chemical and physical properties. First, they are inconvenient for routine verbal communication. The empirical and molecular formulas discussed in the preceding section are precise and highly informative, but they have some disadvantages.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)